Glossary du Cinéma

Aspect Ratio

An Aspect Ratio is the proportional mathematical relationship between the width and height of a rectangle, the rectangle being the image or screen, in the case of movies.

Calculation of a rectangle’s Aspect Ratio is a simple matter of Width to Height, or Width divided by Height, proportional to 1. This relationship is expressed as Width:Height or (Width/Height):1 or (Width/Height) to 1.

For example, the Aspect Ratio of a rectangle 4 inches wide by 3 inches high is written as “4:3” or “1.33:1” (because 4/3 is approximately 1.33), and spoken as “1.33 to 1” or sometimes “one thirty three”.

The 4:3 ratio has traditionally been referred to as “Fullscreen” in the home video market, because a 4:3 image is an exact fit for a cathode ray tube (CRT) television from the days of old, filling the entire screen with not a pixel to spare.

To the right is a stack of rectangles illustrating the most common aspect ratios of movies made during the past century, labeled with some of the terms used to describe them.

See also: Fullscreen, Widescreen, Enhanced for 16×9 Televisions

Cue Marks

Cue marks indicate when it is time for a projectionist to switch to the next reel of a movie that is printed on multiple reels of film. Cue Marks are visible in the top right-hand corner of the frame, and are typically simple geometric shapes, such as squares or ovals. Film may be marked with small holes, scratches, or ink.

Uninterrupted playback of a multi-reel film requires two projectors:

Outgoing Projector – The projector playing the reel that is about to end

Incoming Projector – The projector that will play the next reel after the changeover

Each reel of film has two cue marks, as demonstrated by these screenshots taken from everyone’s favorite Czech spoof of an American western that was made in Czechoslovakia and set in Arizona, Limonádový Joe (Lemonade Joe) :

Motor Cue – Appears 8 to 10 seconds before the end of the reel, indicating that it is time to start the incoming projector

Changeover Cue – Appears about 1 second before the reel ends, indicating that it is time to open the lens on the incoming projector, close the lens on the outgoing projector, and switch the audio source to the incoming projector

Although the Motor Cue Mark is a different shape than the Changeover Cue Mark in this example, this is not always the case. Sometimes both Cue Marks on a film reel look the same, but it is not a problem for the marks to be identical, because it is understood that the first to appear is the Motor Cue Mark and the second to appear is the Changeover Cue Mark.

Movies in digital formats frequently omit the Cue Marks, because no changeover is needed for a digital presentation. However, many DVDs are produced with intact Cue Marks, which are well on their way to being more nostalgic than functional.

Oeuvre

An Oeuvre is the entire body of work produced by an artist in their lifetime.

In the world of cinema, this refers to all of a director’s films, all of a composer’s scores, all of an actor’s roles, etc. An individual artistic work can also be called an Oeuvre, though one would not typically be talking about just one film, score, or role when speaking of someone’s cinematic Oeuvre, unless they only worked on one movie, as the word is most commonly used as a collective term.

Tints and Tones

Before any movie made a sound, before any editor cut a piece of film,

before anyone even thought they could use two camera positions in one motion picture…

…Tints and Tones were turning black & white into color.

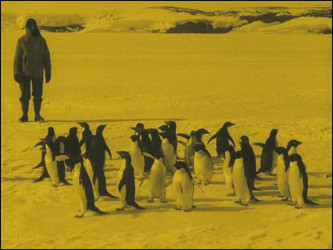

Tinting and Toning are methods of colorizing black & white film. These complementary effects target different parts of the film emulsion, coloring the blacks and whites independently, with a combined effect in the grey areas.

Tint – Colors the transparent areas of the film, most strongly affecting the whites

Tone – Colors the opaque particles on the film, most strongly affecting the blacks

This frame was Tinted to make huge tracts of yellow snow (which should never be eaten).

The penguins’ white feathers were also strongly enhanced by the Tint

Black penguin feathers and the interloping human show very little yellow influence.

This was Toned, making the darkest areas deep blue.

The sky, which goes from lighter to darker shades as altitude increases, becomes blue gradient.

Semi-shaded textures on the ice take on a medium blue cast, while the brightest areas remain white.

In the early 1900s, many films got the Tint/Tone treatment. It was normally done in one of two ways:

The Easy Way – Soak a strip of film in the colorizing solutions, let it dry, and start editing

The Hard Way – Paint one color onto every film frame that needs it, either freehand or with stencils, allow it to dry, and repeat for the next color… and the next… and the next. Oh… and try not to make any mistakes.

Here are some examples of shots that were colorized the easy way. This method produces a very consistent effect, but artistic options are limited to choosing one or two colors.

The Tint and Tone used for this shot were both Orange.

Using the same color on the blacks and whites gives the image a monochrome style that spans the full range of orange shades.

All of the other frames on the same strip of film have the same look. Fortunately, it’s a good one.

Cyan Tint and sepia Tone were used to create this dichromatic color scheme.

The cyan is most vivid on the snow (edibility uncertain), and the light parts of the seals.

Sepia dominates the dark parts of the seals (maybe edible, but don’t), and stays out of the snow.

Next is an example of Tints and Tones done the hard way. The effect is detailed, yet imperfect. It is possible to have more than two colors per frame, but consistency and precision throughout the duration of the shot are unattainable.

Consecutive frames played in slow motion highlight how unique each frame can be.

Hand coloring lacks the uniformity of “the easy way”, but gives the artist more flexibility to be creative.

The fountains illustrate that the color at a given spot can change in every frame, even though that part of the filmed scene never changes.

This color film was produced in 1908! No two copies are identical.

Titles, Title Cards, Intertitles

A Title is onscreen text, and sometimes art, meant to provide information that might not otherwise be learned from a movie’s audiovisual content.

Titles let us “hear” dialogue in silent films, and translate unfamiliar languages. They offer historical context, tell us who worked on the movie, and even show the math comparing reproductive tendencies of smart people and idiots.

The Main Title shows the name of the film. It may be part of a Title Sequence that includes the opening credits and perhaps theme music.

Long ago, almost all Titles were written, typed, painted, or glued onto paper cards, hence the name “Title Cards”. Wood, cloth, and other surfaces sometimes took the place of paper backing, but they were “Cards” nonetheless.

Each card was filmed up close with a stationary camera, and the shots of the cards were added to the movie during editing.

A Title inserted between two shots, interrupting the movie action, is called an Intertitle. Silent film dialogue is almost always expressed using Intertitles.

It was not long before Titles were being made on transparent animation cells or panes of glass, and shot in front of attractive backgrounds or superimposed over projected film images.

Graphics software now makes it easy to skip the steps of creating physical Titles and filming them. Still, film makers occasionally employ older methods for artistic reasons.

Although actual cards are seldom a part of the process these days, the term Title Card remains in use.

Ovoce Stromů Rajských Jíme (Fruit of the Tree of Paradise)

American New Wave, American Renaissance, New Hollywood

The American New Wave, also known as the American Renaissance or New Hollywood, was a film movement in the United States that lasted from the late 1960s to the early 1980s.

.

.

Czechoslovak New Wave

The Czechoslovak New Wave was a film movement that happened during the 1960s and early 1970s in Czechoslovakia. It centered around an eclectic bunch of movies made by a young generation of disaffected Czech and Slovak directors, who used cinema to challenge the political status quo and artistic norms.

Czechoslovak New Wave directors expressed their dissatisfaction with their country’s state of affairs by way of experimentation, metaphor, dissent, and outright subversion of the Communist government that had been making Czechs and Slovaks miserable since the coup d’état of 1948. Not surprisingly, the Communists were not amused, and many of the films were banned, and some of the brash young directors suddenly found it difficult to find work.

Luckily for us, the films were not destroyed, and the bans were lifted when Democracy returned to Czechoslovakia in 1989. Many Czechoslovak New Wave titles are easy to obtain these days, and watching these wonderfully unique movies is HIGHLY recommended.

French New Wave

The French New Wave was a film movement…

.

.

Enhanced for 16×9 TVs, Enhanced for Widescreen Televisions, 16×9 Enhanced

If a movie is said to be Enhanced For 16×9 Televisions, it means that the movie’s aspect ratio is something other than 16:9, and that black bars have been added to the edges, such that the combination of the picture and the black bars forms a 16:9 rectangle. Maybe it sounds crazy to intentionally add unsightly bars to a perfectly nice widescreen display, but it is done for good reason.

On many widescreen TVs, 16:9 is the only supported wide format aspect ratio. Upon receiving a non-16:9 video stream from a DVD player, a TV with that sort of limitation will take it upon itself to reformat the picture. Because the vast majority of films in the known universe are not intended to be in 16:9 format, most existing movies are subject to being stretched, squeezed, or cropped by inept display hardware. As long as the video image can be crammed into a 16:9 rectangle, the TV doesn’t care what it looks like.

A 16×9 Enhanced DVD is not affected by this problem. When a movie and black bars are combined to build a 16:9 rectangle and encoded to DVD, the result is a 16:9 video stream, which will trick a format-challenged TV into believing that the movie is already 16:9 and needs no reformatting, thereby preserving the movie’s original aspect ratio despite the TV’s inherent limitations.

It is easy to illustrate the image quality advantage that a 16×9 Enhanced DVD has over non-enhanced DVD. Below are two presentations of the same frame from Citizen Kane. On the left, the original 4:3 image has been reformatted to 16:9, in the manner of an overzealous widescreen TV, causing much distortion as evidenced by the elliptical snowball and stretched faces. The 16×9 Enhanced image on the right is free of distortion, as we can see by the snowball that is round and the people that don’t look like mutants.

Now look at a frame from Chinatown. The movie’s original format is a very wide 2.35:1, however the non-enhanced image on the left is squeezed horizontally so that it fits into a 16:9 rectangle. Distortion is made obvious by the mirror, which is supposed to be round, as it is in the 16×9 Enhanced image on the right.

Not all widescreen displays are designed to ruin the appearance of movies. Some have no trouble with movies that are not 16×9 Enhanced. The ones that do cause problems may employ different methods of image abuse, so the key is to understand the workings of the specific TV and DVD player being used, as well as the enhancement features, or lack thereof, encoded onto the disc being played.

If all else fails, and a proper widescreen picture cannot be obtained from a non-enhanced DVD, try switching the TV’s display format to 4:3, and setting the DVD player to 4:3 Letterbox mode. That will cause the sides of the screen to remain unused, but the movie will look the way it was meant to look, which is much more important than fulfillment of one’s widescreen manifest destiny.

See also: Aspect Ratio, Fullscreen, Widescreen

Fullscreen, Full Frame

Fullscreen refers to video that has been formatted to fill the entire screen area of a television or monitor, without added black bars.

In conventional use, the screen to be filled with Fullscreen video is an old style tube television, which has an aspect ratio of 4:3. Movies labeled Fullscren or Full Frame are usually in 4:3 format, an exact fit for old television screens.

Because video formatting issues are not confusing enough, some DVD and Blu-ray distributors have begun to use Fullscreen or Full Frame labeling on movies in 16:9 format, which fits today’s widescreen displays, but not old TV screens. Sometimes the labeling makes it clear which definition of Fullscreen is being used, and sometimes the customer gets to guess (it’s not just a movie, it’s also a game!) The way of the dingo is to assume Fullscreen means 4:3 unless otherwise specified.

See also: Aspect Ratio, Widescreen, Enhanced for 16×9 Televisions

HD, High Definition Video

High-Definition Video (HD) is video formatted in a higher resolution than NTSC (480i) and PAL (576i), which are considered standard-definition formats. HD is a term that represents a variety of video modes. Although each HD video mode is defined by its own combination of resolution, scanning system, and frame rate, one they all have in common is a 16:9 Aspect Ratio.

HD Resolution (e.g. 720, 1080) indicates the number of pixel rows (vertical pixel count) used to display the image. The horizontal pixel count is normally omitted, but it can be mathematically derived from the vertical pixel count and the aspect ratio:

Horizontal = 16 Vertical / 9

The scanning system is either progressive (p) or interlaced (i). Progressive systems refresh the entire image in one pass, drawing every row of pixels in a single refresh operation. Interlaced systems refresh only half of the rows at once, drawing a field of odd-numbered rows in one pass, and then drawing a field of even-numbered rows in another pass.

Frame Rate (e.g. 23.97, 24, 25, 60, 120) is the number of frames drawn per-second (Hz). An interlaced system has a Field Rate, which is typically of twice its Frame Rate, because two fields are drawn per frame. The refresh rate advertised for a specific HDTV may or may not be the same as the Frame Rate of any particular video mode. Careful scrutiny of the numbers, and how they are expressed, is key to knowing what is in the box.

Generally speaking, higher resolutions, higher frame rates, and progressive scanning produce sharper images and smoother motion. But keep in mind there are many other factors that contribute to video quality, or lack thereof. For example, too much sharpness can make a movie, which was shot on film, look like it was shot on video the 1980s.

See also: NTSC (480i), PAL (576i)

NTSC, 480i

In home video terms, NTSC refers to the 480i analog video standard used by CRT (tube) televisions, VCRs, and DVD players throughout North America, and a few countries in South America, east Asia, and the Pacific ocean. If you have a tube TV or monitor in the United States, it is almost certainly an NTSC display, which needs an NTSC signal in order to show a picture.

Video tapes and DVDs manufactured for sale in America are NTSC encoded, and can only be played by NTSC compatible players. Most VCRs sold in America play only NTSC video tapes and produce only NTSC output. Some DVD players in the US are similarly limited, though it is becoming common for them to play DVDs encoded in either NTSC or PAL format, and to offer multiple output formats, most notably HD. Blu-ray discs are not encoded in NTSC format.

The NTSC video format consists of a series of video frames. An NTSC video frame represents an image that fills the entire display, which has 480 visible scan lines (rows of image data). Each video frame is made of two interlaced video fields, meaning each video field contains only half of the scan lines needed to make a complete image. The first field in an NTSC frame contains only the even-numbered scan lines, and the second field contains only the odd-numbered scan lines. When the video is displayed, each video field is drawn on the screen in a separate drawing operation (pass). The even-numbered rows are drawn in the first pass, and then the odd-numbered rows are drawn in the second pass. And so it goes that the result of each drawing operation looks like a picture that has been combed, but the process happens so quickly that the human eye sees a normal, complete picture.

During the film-to-NTSC Telecine process, duplicates of some of the video fields are inserted in to the video stream, a technique known as 3:2 Pulldown. This is done because most films run at 24 frames per second, while NTSC runs at 29.97 frames per second, and without compensation for the difference in frame rates, the video version of the movie will go through almost six extra frames per second, a speedup of nearly 25%. The repeated video fields have a slowing effect, but also reduce smoothness by causing a bit of visual distortion called “telecine judder.”

See also: PAL (576i), HD, Telecine

PAL, 576i

In home video terms, PAL refers to the 576i analog video standard used by CRT (tube) televisions, VCRs, and DVD players in many parts of the world outside of North America. If you have a European tube TV or monitor, chances are that it supports PAL and not NTSC.

Video tapes and DVDs manufactured for sale outside of North America are usually PAL encoded, and can only be played by PAL compatible players. Some DVD players sold in PAL-friendly countries play only PAL encoded DVDs, and produce only PAL output, though it is becoming common for them to play DVDs encoded in either PAL or NTSC format, and to offer multiple output formats, most notably HD. Blu-ray discs are not encoded in PAL format.

The PAL video format consists of a series of video frames. A PAL video frame represents an image that fills the entire display, which has 576 visible scan lines (rows of image data). Each video frame is made of two interlaced video fields, meaning each video field contains only half of the scan lines needed to make a complete image. The first field in a PAL frame contains only the odd-numbered scan lines, and the second field contains only the even-numbered scan lines. When the video is displayed, each video field is drawn on the screen in a separate drawing operation (pass). The odd-numbered rows are drawn in the first pass, and then the even-numbered rows are drawn in the second pass. And so it goes that the result of each drawing operation looks like a picture that has been combed, but the process happens so quickly that the human eye sees a normal, complete picture.

When a film is converted to PAL video, the Telecine process does nothing to compensate for the difference in frame rates between most movies, which run at 24 frames per second, and the 25 frames per second PAL frame rate. This results in the video version of the movie playing back 4% faster than the film version, a phenomena known as PAL Speedup.

See also: NTSC (480i), HD, Telecine, PAL Speedup

PAL Speedup

PAL Speedup a side effect of the process used to convert films shot at 24 frames per second to PAL video format.

PAL video runs at 25 frames per second, while most movies are shot at 24 frames per second. Unlike film-to-NTSC conversions, in which frames are duplicated to compensate for the difference in frame rates, the film-to-PAL conversion is a straight frame-for-frame copy. As a result, PAL encoded movies go through one extra frame each second as compared to 24 FPS films. Therefore, the running time of the video is 4% shorter than that of the film, and the audio is slightly higher in pitch, unless corrected.

It might seem like a lazy way to do a conversion, but there are benefits. In addition to PAL encoded movies giving viewers 4% more time to watch other movies, PAL videos are more smooth than NTSC videos, in which the repeated frames cause a bit of distortion known as “telecine judder.”

Telecine

Telecine is a process by which motion picture images shot on film are transferred to video.

In order to get film into a computer for editing, or onto a Blu-ray for you to buy, it must be converted into a digital format. The procedure and tools used can vary depending on the desired format and the equipment available, however, the basic idea is that light shines through each frame of the film, and onto a sensor that records the image data. The full frame can done at once by a big light, or a small light can pass over a little bit of the frame at a time until the whole frame has been scanned. Sometimes prisms are used to separate the primary colors, or different colored LEDs are flashed and picked up by color-aware sensors. Frame rate issues are dealt with depending on the difference between the film’s frame rate and that of the destination format.

Not surprisingly, the equipment, methods, and care employed by the people who do Telecine work will have a significant effect on the look of the transfer, for better or worse. Ultimately, this can be the difference between happy film fans abuzz with excitement about a high quality DVD release, and disappointed film fans who can only hope for something better in the future.

See also: NTSC, PAL, PAL Speedup

Widescreen

Widescreen refers to film and video images where the proportion of width to height is greater than Academy Ratio, which is 1.37:1. To calculate the image proportion, simply divide width by height. Some of the most common Widescreen proportions include 1.66:1, 1.78:1, 1.85:1, 2.35:1, and 2.39:1.

See also: Aspect Ratio, Fullscreen, Enhanced for 16×9 Televisions